INTOXICATING SPRING GARDENS FROM STRATFORD-UPON-AVON TO SOUTH LONDON

Anne Hathaway’s Cottage Garden – a sculptural philadelphus ‘tree’, a sweet-scented riot of tulips and new perennial foliage

Anne Hathaway’s Cottage Garden – a sculptural philadelphus ‘tree’, a sweet-scented riot of tulips and new perennial foliage

Charles Rutherfoord’s headily fragrant South London garden – a sculptural laburnum tree, a border of stepover apples and brilliantly coloured tulips

Charles Rutherfoord’s headily fragrant South London garden – a sculptural laburnum tree, a border of stepover apples and brilliantly coloured tulips

I have badly wanted to visit the houses and gardens of Stratford-upon-Avon since reading Frank Lawley’s inspirational book on the making of his exquisite Northumberland garden, Herterton (see my October 2015 blog post).

For Frank and his wife Marjorie, the gardens at Anne Hathaway’s Cottage and Mary Arden’s Farm triggered an understanding, a recognition even, that a relaxed, abundant style of planting, anchored by architectural trees and shrubs, was just the kind of intimate, uplifting garden they wanted to create. (Anne Hathaway became Shakespeare’s wife, and Mary Arden was his mother).

‘Perhaps our greatest discovery was in Stratford-upon-Avon. It was not the river nor the theatre but the entrancing group of places belonging to the Shakespeare Birthplace Trust . Following signs through the suburban edges of the town, dodging traffic, a long stretch of clipped hawthorn hedge … confronted us. Along the pavement beside it, a crocodile of Japanese visitors was approaching this English shrine that is Anne Hathaway’s Cottage … the garden planting was unsophisticated: here were the daisies, thrift and pinks we knew. The house border had clipped yews and ivy and the profuse white rose, Rosa alba.

And three miles away another long old farm, Mary Arden’s House, stood closely beside its lane. Just inside its low wall, warmly furnished with red valerian, there was just space for a very organic thin parterre. The box was well cut, but it had long forgotten any concept of horizontal tops and matching vertical sides. It bulged and spread, denying any entry by path. An odd delphinium was trapped inside. The very narrow house border had topiaries shrubs, this time with clouds of the old pink and purple ‘everlasting’ sweet pea.’

Herterton House Garden – bulging hedges and tousled planting

Herterton House Garden – bulging hedges and tousled planting

At last, dreaming of bulging hedges and tousled native flowers, I head off to Stratford at the end of April. It is a bit of a jolt to arrive at Shakespeare’s New Place and be greeted by immaculate stretches of hard landscaping, a glittering ‘Tempest’ themed galleon, and shiny bronze raised beds with primary coloured pennants representing all thirty-eight of Shakespeare’s plays.

The Golden Garden, Shakespeare’s New Place, with pennants representing Shakespeare’s thirty-eight plays

The Golden Garden, Shakespeare’s New Place, with pennants representing Shakespeare’s thirty-eight plays

But this is just the beginning. I am nearly down with one blow at the sight of the monumental bronze tree ‘bent under the force of Shakespeare’s power of imagination’, with its tortured branches hovering over a potent looking ‘celestial sphere’.

The bronze tree ‘bent under the force of Shakespeare’s imagination’

The bronze tree ‘bent under the force of Shakespeare’s imagination’

But then I listen more attentively to the historian from the Shakespeare’s Birthplace Trust and realise that I have made the same mistake as many visitors. Shakespeare’s New Place is the site of the extensive house and grounds Shakespeare bought for his family and lived in from 1597 until his death in 1616, but the house itself no longer exists. The building we take to be Shakespeare’s house is in fact Nash’s House, the home of Thomas Nash who married Shakespeare’s granddaughter. New Place was, rather astoundingly, demolished by a Rev. Francis Gastrell who, on buying the house in 1753, became so infuriated by visitors asking to see the mulberry tree reputed to be planted by the bard that he cut the tree down in 1758 and knocked the house down the following year, much to the fury of locals and worldwide admirers alike.

Shakespeare’s Birthplace Trust was established in 1847, following a campaign with vigorous support from luminaries such as Charles Dickens, to save Shakespeare’s home for the nation and is now custodian of an enormous world class collection and archive. To celebrate the 400th anniversary of Shakespeare’s death the garden at New Place has been given a substantial and – despite my initial sense of surprise – deeply thoughtful overhaul. Archeological investigations have established for the first time the footprint of Shakespeare’s house and outbuildings and these are discreetly marked out in elegantly engraved bronze strips. Every element is a tool for story telling to make the past come alive. I loved discovering that the feisty Anne Hathaway ran her own successful malting business from buildings in what is now the Great Garden.

Engraved bronze strips embedded in the paving mark the footprint of Shakespeare’s house, barns and outbuildings

Engraved bronze strips embedded in the paving mark the footprint of Shakespeare’s house, barns and outbuildings

A circle of pleached English Hornbeam marks the position of the house, offering a fitting structure and the feeling of shelter for a set of magnificent curved oak benches – space to sit for some of the 825,000 visitors each year to the Trust’s properties. The benches were made with the help of local students by Warwickshire cabinet maker Armando Magnino.

A circle of pleached hornbeam offers structure and shelter to a set of magnificent locally made curved oak benches

A circle of pleached hornbeam offers structure and shelter to a set of magnificent locally made curved oak benches

Glyn Jones – whose immaculate pedigree includes working alongside Penelope Hobhouse at the seventeenth century Tintinhull and many years as Head Gardener at Hidcote – has been appointed as Head of Gardens. He has five Stratford Gardens in his care: Shakespeare’s Birthplace, New Place, Anne Hathaway’s Cottage, Mary Arden’s Farm and Hall’s Croft, the home of Shakespeare’s daughter, Susannah, and her husband Dr John Hall which is to have a newly designed physic garden. He admits that the gardens have become a little too uniform over the years and he has plans to develop their individuality and to encourage creativity and experimentation.

Wisteria against the soft red brick walls of Nash House

Wisteria against the soft red brick walls of Nash House

Despite the demanding scale of his brief, you cannot fail to have faith in a man who looks with fatherly tenderness at the imposing elegance of the pleached hornbeam and describes his relief that each tree has come happily into leaf this spring as they were seed grown and as such there were ‘no guarantees’. He offers a similar almost wistful concern for the long established mauve wisteria trained in a happy tangle against the soft red brick of Nash’s House. ‘That’s Chinese Wisteria, Wisteria sinensis. Japanese wisteria (Wisteria floribunda) would have been a better choice – it is more fragrant and comes into flower later and so is less likely to be hit by frost’.

For me, the New Place garden gets really interesting in the next section where a newly renovated Sunken Knot Garden lures the visitor on with its subtle order and soft tapestry of santolina, hyssop, thyme, standard roses and dusky Tulip ‘Queen of Night’.

The Sunken Knot Garden at Shakespeare’s New Place

The Sunken Knot Garden at Shakespeare’s New Place

Paths have been unobtrusively widened for full disability access and the original arched ‘bower’ which runs down one side – a sort of rounded pergola – has been lovingly rebuilt in oak and the old crab apples (some 100 years old) carefully repositioned over their new frame.

The fine new oak Bower with openings for benches from which to look onto the Knot Garden

The fine new oak Bower with openings for benches from which to look onto the Knot Garden

The walls and fences on the other three sides of the Knot Garden are clothed, as befits the archetypal knot garden, in productive plants and every detail is beautifully arranged. I love the way the spreading wall-trained fig is lushly underplanted with a simple combination of silvery-blue iris and inky tulips.

The Knot Garden wall clothed in a fan trained fig underplanted with iris and tulips

The Knot Garden wall clothed in a fan trained fig underplanted with iris and tulips

Euonymous japonicus ‘Green Rocket’ has been used with great success instead of box to mark out the shapes and edges of the knot garden. ‘It is not as tight as box’ admits Glyn ‘but it looks very good’. Garden designers have become reluctant to specify box for new gardens because of the blight which has ravaged so many European and now New Zealand and US gardens, and long established gardens such as Sissinghurst are growing stocks of this kind of Euonymous as a back up should the worst happen. However, the cheerful neatness of this ‘Green Rocket’ encourages me to suggest a knot garden – or at least formal evergreen edging – the next time an opportunity arises.

Euonymous japonicus ‘Green Rocket’ (with thyme above) providing a smart bright green edging to the Sunken Knot Garden, New Place

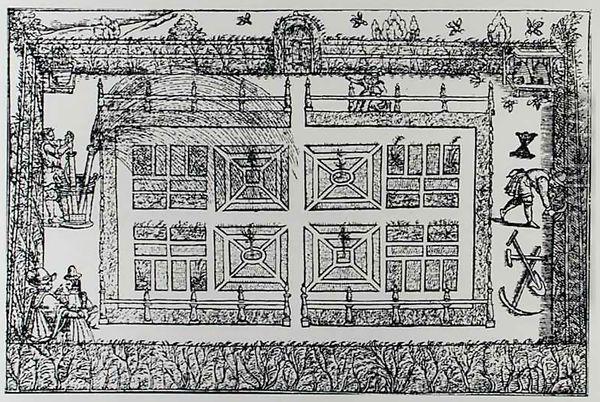

As I am mulling over elaborate possibilities for creating my own intricate Elizabethan knot garden, I have the rug pulled again from under my feet when I learn that the original Sunken Knot Garden at New Place was only installed in 1922. It is clear that Shakespeare was familiar with knot gardens – there is a ‘curious knotted garden’ in Love’s Labours Lost and in Richard II the whole of England is described as a garden in a state of neglect: ‘the whole land/Is full of weeds, her fairest flowers choked up/Her fruit trees all unpruned, /Her knots disordered, and her wholesome herbs/ Swarming with caterpillars’… But it was an eminent Edwardian garden historian, Ernest Law who set about designing ‘a sunken parterre’ for New Place, convinced that the addition of a historically accurate garden of the kind Shakespeare would have known would be an important and illuminating addition. The Trust has in its collection an original copy of Thomas Hill’s ‘The Gardener’s Labyrinth’, regarded as the first English gardening book, which has detailed guidance and templates for the shapes of knot gardens Law could have used. But, as Roy Strong sets out in his 2016 book ‘The Quest for Shakespeare’s Garden’ (which I have to tell you, includes a well observed and very funny chapter on Lucia’s ‘Shakespeare’s Garden in E.F. Benson’s Mapp and Lucia), Ernest Law was ambitious for something special. As well as drawing inspiration for ‘balustrades of Warwickshire elm’ and a ‘dwarf wall, of old fashioned bricks – hand-made, sun-dried, sand-finished’ from Thomas Hill’s work, he sourced his four knot designs from ‘Mountaine’, ‘Gervase Markham’s ‘Country Housewife Garden’ (1613) and William Lawson’s ‘New Orchard and Garden (1618). Donations for the Knot Garden included plants from major UK botanic gardens plus four standard roses from different members of the Royal Family to stand at the centre of each square. The garden is notable as the first attempt at recreating a historic garden and opened the door to Garden History as a rich and revelatory subject.

An illustration from Thomas Hill’s The Gardener’s Labyrinth showing a hand pump for watering

An illustration from Thomas Hill’s The Gardener’s Labyrinth showing a hand pump for watering

Roy Strong’s ‘The Quest for Shakespeare’s Garden’ published for the 400th year anniversary of Shakespeare’s death

Roy Strong’s ‘The Quest for Shakespeare’s Garden’ published for the 400th year anniversary of Shakespeare’s death

Finally to the Great Garden – an acre and a half of lawn, spreading mulberry trees (more stories – for another time perhaps) and 295 feet of tremendous bulging yew hedges!

Tremendous bulging yew hedges and buttresses at New Place

Tremendous bulging yew hedges and buttresses at New Place

Unsurprisingly perhaps, these hedges are another test for the lens through which we view historic gardens. Despite the great age suggested by the uneven, spreading bulk of these glorious stretches of yew, with their substantial buttresses marking out broad beds for herbaceous plants, they were in fact only planted in the 1920’s, and the shape of the borders was developed with advice from the great Edwardian plantswoman Ellen Willmott. The hedges were also crucial in Ernest Law’s eyes to hide the formal Victorian cast iron railings that ran the length of the garden and were doing nothing to help bring a Tudor garden to life. Head of Gardens, Glyn Jones eyes up the hedges and explains that they would have first lost their crisp, ordered shape during the Second World War when the gardeners went off to fight. He wonders for a moment (with a Hidcotian glint in his eye?) if the correct thing to do would be to restore them to their original 1920’s proportions. Horror! For me – and clearly for the rest of the group – the hedges as they are now are a key pleasure of New Place and help the gardens feel anchored and settled despite the great bustle that goes on all around them.

The garden is suddenly flooded by a group of French school children. I smile at the proprietorial way a girl stands before the hedge they call ‘The Elephant’ to photograph her friends in the cave-like inside. The garden – with its fine hedges – is robust enough to take it.

The garden is suddenly flooded by school children

The garden is suddenly flooded by school children

Taking a photograph of The Elephant

Taking a photograph of The Elephant

It is a twenty minute walk from New Place to Anne Hathaway’s Cottage at Shottery. In Shakespeare’s time Shottery was a separate hamlet to which the young eighteen year old would head (Macron-style) to woo Anne who was twenty six. But now it is situated just at the edge of town. You follow a path up to the Cottage with a just- seen Shottery Brook on your left screened by a rather beautiful, unashamedly Ophelia-resonant, living willow fence.

The living willow fence which screens Shottery Brook

The living willow fence which screens Shottery Brook

It feels rather surreal to be finally arriving at such an iconic place, not least as I realise again that the thing to grasp is the complex layering of time. What we are about to see is a house that would have stood in Shakespeare’s day and a garden that is our 21st Century interpretation of a late Victorian/Edwardian notion of a cottage garden. A more natural look and a celebration of simple native plants had been made popular by the persuasive words of William Robinson in books such as ‘The English Flower Garden’ (1883) and so, when drainage improvements were made to Anne Hathaway’s Cottage in the early 1920’s, Ellen Willmott was asked to redesign the garden. You are likely to have heard of ‘Miss Willmott’s Ghost’ – the silvery sea holly (Eryngium giganteum) named for the imposing plantswoman’s supposed habit of scattering seeds secretly in other peoples’ gardens. How stories turn into other stories: I was rather taken aback to see the entry for Eryngium giganteum on the Chiltern Seed website with the advice that as it is a ghostly coloured plant ‘grow it and scare your friends!’ … Eryngium giganticum – Miss Willmott’s Ghost

Eryngium giganticum – Miss Willmott’s Ghost

The approach to Anne Hathaway’s Cottage

The approach to Anne Hathaway’s Cottage

Glyn Jones has many plans afoot to invigorate and further sweeten the garden at Anne Hathaway’s Cottage. His first idea is to slow down the visitor’s arrival so that instead of seeing the house straight away over the garden hedge, they approach it more slowly – and more romantically – through the orchard. He and his team are already hard at work trying to relax the orchard – the grass has been over-fertilised and needs to be stripped of nutrients and sown with yellow rattle to achieve the mown-paths-through-long-grass look that is as desirable today as it was a hundred years ago. He is letting the surrounding hedges grow loose for the next three years with a view to laying them properly when there is enough new growth.

The Orchard in the grounds of Anne Hathaway’s Cottage

The Orchard in the grounds of Anne Hathaway’s Cottage

There is already a successful programme of vegetable growing using varieties that would have been available in Edwardian times. Nestling into the low hawthorn hedges, they help anchor the cottage in a timeless seasonal pattern.

Traditional vegetables at Anne Hathaway’s Cottage

Traditional vegetables at Anne Hathaway’s Cottage

When our group is finally standing before the perfectly thatched cottage with its three broad borders of jewel-coloured tulips emerging from the luxuriant new foliage of herbaceous perennials, it has just stopped raining and we are all grinning from ear to ear to be amongst this sea of fresh and fragrant colour. Glyn Jones tells us that his team has been taking cuttings from the now tree-like Philadelphus (mock orange) by Ellen Willmott near the house and how they will be echoing her method of blending the ornamental into the wild. She used to plant ornamental shrubs into the hedgerows, at first one shrub every few yards and, as you got further from the house, perhaps one shrub every twenty yards, so that the transition was barely noticeable.

Anne Hathaway’s Cottage borders filled with tulips, a tree like Philadelphus now almost as tall as the house

Anne Hathaway’s Cottage borders filled with tulips, a tree like Philadelphus now almost as tall as the house

He explains how the Willmott-designed borders are going to be meticulously cleared and replanted one at a time:

The first of three borders lying fallow as it is cleared of weeds before replanting

The first of three borders lying fallow as it is cleared of weeds before replanting

Glyn wraps up by airing his worry about the tulips: surely they are too much of a muddle, not of the period, too garish? …. There is an outcry!

The riot of tulips and fresh foliage in one of the borders in front of Anne Hathaway’s Cottage

The riot of tulips and fresh foliage in one of the borders in front of Anne Hathaway’s Cottage

My group all love the technicolour buzz of the place and cannot bear the idea of a filter of perfect taste being applied to future plantings. But caring for this kind of iconic garden, considering what might be historically accurate, respecting the input of other passionate gardeners over the years and leaving room for some contemporary creativity is a demanding balancing act . I will definitely be back to see the gardens as they are guided into the future by such a fine and thoughtful gardener.

The borders at Anne Hathaway’s Cottage remind me – almost uncannily – of the wonderfully intense garden I have just visited in London.

Charles Rutherfoord’s Garden – an exhilarating, scented kaleidoscope of tulips and step-over apple trees.

Charles Rutherfoord’s and Rupert Tyler’s Clapham garden had an almost identical, giddying impact on the 250 or so NGS visitors on a late April afternoon. In a private garden, of course, a sense of excitement of entering a different world can be created and enjoyed with utter freedom. I love the way that Charles and Rupert just go for it. This is a celebratory garden where thousands of tulips, voluptuous tree peonies and velvety iris blaze away with abandonment at the back of their sleekly elegant house. The peonies alone make you want to hit the Kelways website to order the voluptuous, rich pink Japanese tree peony ‘Cardinal Vaughan’ as soon as you get home.

Paeonia ‘Cardinal Vaughan’ amongst tulips and irises

Paeonia ‘Cardinal Vaughan’ amongst tulips and irises

I am riveted to discover that – as well as the glowing pink tulip ‘Mariette’ which Charles has planted for the first time and the dark foil of tulip ‘Queen of Night’ – the red and yellow flamed tulips which light up the display are in fact tulips which have just emerged this way – older tulips with a virus. ‘It’s so exciting. Last year there were one or two, now the whole space is filled with them’.

This is a garden that is gardened intuitively by a passionate and knowledgeable plantsman. ‘I only really think about the garden when I am working in it. I move plants around and put them where they feel right. He does not remember consciously arranging the three groups of rich purple iris, but enjoys the fact that they have found perfect places – two clumps flanking the step-over apple border to the tulip bed and a third clump in a slightly different part of the garden, serving as a comfortable echo.

Paths to take you round the garden are developed in a similar hands-on, organic way with a section of sun-warmed path made from raised sleepers forming a central axis under the yellow glow of a laburnum tree, a handsome path of stone and brick flanked by the stepover apples and mounds of rosemary and new curving path of reclaimed yellow brick lighting up a shady tunnel under the weeping branches of Acacia pravissima.

Hand built paths of railway sleeper, stone and brick paths flanked by apple trees and rosemary and a curved brick path through a shadier part of the garden

Hand built paths of railway sleeper, stone and brick paths flanked by apple trees and rosemary and a curved brick path through a shadier part of the garden

I love the contrast of the painterly feel of the garden with the restrained perfection of the house interior and the way that the garden fills the windows with such generosity.

Painterly view from the top floor of the house – the sculptural, weeping branches of Acacia pravissima in the foreground. The grey leaved tree behind it is Acacia baileyana ‘Purpurea’

Painterly view from the top floor of the house – the sculptural, weeping branches of Acacia pravissima in the foreground. The grey leaved tree behind it is Acacia baileyana ‘Purpurea’ The rear of the garden with a delightful tapestry of Cercis canadensis, Cotinus ‘Grace’ and more flamed tulips

The rear of the garden with a delightful tapestry of Cercis canadensis, Cotinus ‘Grace’ and more flamed tulips

The immaculate, elegant interior of Charles Rutherfoord and Robert Tyler’s house with views through to the abundant garden. House & Garden May 2017 edition, photographs by Michael Sinclair

The immaculate, elegant interior of Charles Rutherfoord and Robert Tyler’s house with views through to the abundant garden. House & Garden May 2017 edition, photographs by Michael Sinclair

Euphorbia mellifera is used wonderfully throughout the garden as a relaxed, deliciously honey-scented architectural plant – here with its bronze flowers providing delightful contrast to the ceanothus and borrowed wisteria behind:

And here with the canopy of large specimens lifted so that you can walk underneath and enjoy the light shining through:

There are mounds of acanthus and huge-leaved rosettes of Echium pininana all over the garden which will provide soaring structure later in the season. And everywhere, there is the refreshing use of yellow! An inherited laburnum tree has been flat-topped so as not to restrict the view from the house and has become is a sunny, sculptural presence at the heart of the garden.

The flat topped Laburnum tree at the heart of the garden

The flat topped Laburnum tree at the heart of the garden

The laburnum lights up the comparatively austere back of the house – and its flat top provides a cheerful tiered staging effect for the theatrical row of dancing tulips on the balcony above.

Laburnum and dancing tulips against the house

Laburnum and dancing tulips against the house

Mounds of deliciously scented, paler yellow Coranilla valentina subsp. glauca ‘Citrina’ flank the sleeper path. This is my new favourite must-have plant (after the tree peonies) for its structure as well as its early colour and fragrance:

Coranilla valentina subsp. glauca ‘Citrina’ flank the sleeper path (with an already surging echium front right)

Coranilla valentina subsp. glauca ‘Citrina’ flank the sleeper path (with an already surging echium front right)

And in delightful, shadier spaces, the curving stems and rich yellow lantern-like bells of Brugmansia suaveolens (Angel’s Trumpets) light up the shadows:

Brugmansia suaveolens Angels Trumpets

Brugmansia suaveolens Angels Trumpets

There is a fine yellow tree peony (Paeonia lutea var. ludlowii ) also just opening in the shade – a less showy tree peony to be remembered for its fine architectural leaves – and a rare yellow, wonderfully fragrant honeysuckle Lonicera ‘Anne Fletcher’ draped over a clever screen made of sleepers which divides the garden and creates a discreet place for a table and chairs:

Paeonia lutea var. ludlowii

Lonicera ‘Anne Fletcher’

Lonicera ‘Anne Fletcher’

The clever screen – tall enough to really feel hidden away but light enough to see through – made of railway sleepers

The clever screen – tall enough to really feel hidden away but light enough to see through – made of railway sleepers

The glass table is the first piece of furniture Charles designed. He has made many pieces of indoor furniture: it would be fantastic if he would consider making outdoor furniture too. I love this curved oak slatted seat and footstool. Next step a bench in the same elegant, rustic/industrial style?

Oak seat and foot stool designed by Charles Rutherfoord

Oak seat and foot stool designed by Charles Rutherfoord

The garden is full of much loved individual touches. There are exquisite plants Charles has fallen for which intrigue close-up but have a surprisingly easy going presence within the garden as a whole. This finely veined pink camellia for example (which I think is Camellia japonica ‘Lady Vansittart’) or the white-edged purple lilac ‘Sensation’ which billows in soft clouds in one corner of the garden.

Camellia japonica ‘Lady Vansittart’

Camellia japonica ‘Lady Vansittart’

Lilac ‘Sensation’

Lilac ‘Sensation’

And there are covetable pieces of sculpture, my favourite are a pair of stone finials of shooting flames which Charles has placed to frame the view of the garden from the balcony. I love the simplicity and strength of the flames and their robust stands – they could almost be contemporary but they are Italian Baroque – from a church or bishop’s palace perhaps.

One of a pair of baroque stone finials which frame the view down to the garden

One of a pair of baroque stone finials which frame the view down to the garden

Fascinatingly – and fitting for a story about gardens which have many layers – these finials were used by Cleve West in his 2012 Chelsea Garden and bought by Rupert for the garden when the show garden was dismantled. Cleve West had used them brilliantly at the top of Arts and Crafts influenced gate posts – so when the flames arrived in Clapham the bulbous stands were an added bonus.

Cleve West’s 2012 Chelsea Garden for Brewin Dolphin

Cleve West’s 2012 Chelsea Garden for Brewin Dolphin

Nestled at the end of the tulip border is a rather space age Solardome greenhouse. Inside, on beautiful hardwood shelving (of course), are succulents, pelargoniums and a happy lemon tree with impossibly fat lemons. The centre of the greenhouse is filled with huge containers of dahlias just coming into leaf – ‘purples and oranges, mostly cactus varieties’. These will replace the tulips for the summer. There is something magical about looking out onto the exuberant garden through the misty geometric panes.

Succulents and a lemon tree in the greenhouse with glimpses of the exuberant garden beyond

Succulents and a lemon tree in the greenhouse with glimpses of the exuberant garden beyond

How extraordinary to have seen so many centuries of intense English spring garden in the space of just a few days. I could not have done more even with my own time travel machine.

Charles Rutherfoord’s and Rupert Tyler’s Solardome Greenhouse

Charles Rutherfoord’s and Rupert Tyler’s Solardome Greenhouse

Non, Thank you very much indeed for this article full of wonderful ideas. You have made me want to visit these gardens next spring. I help tend the Shakespeare Garden at the University of the South in Sewanee Tennessee where we have a second home. This garden has 30 plants mentioned by Shakespeare with markers giving the quote and citation. It is a wonderful garden for contemplation. I will send a picture of it this summer. All the best to you, June Mays

Sent from my iPhone

>

Thank you so much, June. Definitely visit the five gardens at Stratford-upon-Avon next year – they are going to get better and better! I love the idea of your Tennessee Shakespeare Garden. Yes please send a picture in the summer. Very best wishes Non

Just discovered your site. Full of wonderful ideas, historical connections, beautiful places. Poetry goes so well with gardening. Sadly, I’m unable these days to visit gardens, but I love reading about them. I will have to come again! Thank you.

–Richard

Dear Richard what a wonderful comment, thank you. I am sorry that you cannot get out to visit gardens these days but am so glad you can join me as I visit gardens and try to communicate what I am noticing. An uplifting message, thank you, all the best Non