BALLETIC ROSE PRUNING, CRISP STRUCTURAL PLANTING, PREPARING FOR ‘THE EXTRAVAGANCE OF SPRING’

Immaculately choreographed, pruned stems of Rosa mulliganii against the sky, The White Garden, Sissinghurst.

Effervescent – also beautifully choreographed, obviously – Burns Night Haggis Dinner in Peckham given by Jake Tilson, Jeff Lee and their daughter Hannah Tlison (above).

The Top Courtyard, Sissinghurst Castle, the walls laced with the curving stems of pruned roses.

The Top Courtyard, Sissinghurst Castle, the walls laced with the curving stems of pruned roses.

I am standing at the entrance to Sissinghurst Castle barely able to keep myself away from leaping over the box hedge and forensically examining the wall ahead of me. It is almost the last day of January. The glowing end-of-winter Burns night festivities are over and after a freezing couple of weeks – down to -7ºC here in Kent – the weather has become milder and there is a feeling that things in the garden are beginning to get on their way. I am with Sissinghurst Head Gardener, Troy Scott Smith, who bends down gently to point out the emerging shoots of peonies – for now just tiny dashes of carmine red against velvet brown soil. He is describing how it feels to be in the garden at this time of year “There is something nice about a quiet spell. I think gardens that are open to the public need it. There is something wholesome about that full cycle, the contrast with the extravagance of spring and summer”.

Troy has generously agreed to show me the garden in winter and knows I am dead keen to start with the roses.

The entrance to Sissinghurst Castle, Rosa ‘Alister Stella Gray’ against the brick wall.

The entrance to Sissinghurst Castle, Rosa ‘Alister Stella Gray’ against the brick wall.

To the right of a brick arch there is an eighty year old ‘Golden Rambler’, Rosa ‘Alister Stella Gray’. Peter Beales describes it as ‘ a repeat-flowering Noisette rose with cascading clusters of double, shapely flowers, yellow with ‘eggy’ centres paling to cream and eventually white at the edges. Highly perfumed and producing long, slightly spindly branches ideal for arches and trellises’. It is wonderful to see how carefully and cleverly the rose has been pruned for maximum coverage and softly-falling flowering. Long stems are retained and curved to form softly rounded steps and counter-steps against the wall. There are plenty of the horizontal stems (necessary for maximum flowering), but the whole system is flowing rather than rigid, as so much rose-pruning tends to end up. These gentle shapes will be entirely achievable (I tell myself) if I look hard enough at these images and use them as a guide next time I head out into the garden with my secateurs ….

I feel a little pressurised to learn that rose-pruning at Sissinghurst is almost over – indeed pruning began on October 15th! The climbing roses against the walls go first – ‘for two reasons: first it is cold and windy high up, second we can clear the beds after pruning at the right time of year.’ Troy uses the classic Nutscene garden twine (in green) and was so frustrated with the flimsiness/garishness of modern vine eyes that he had a mould made of an old one and now a blacksmith keeps the garden supplied with these bespoke chunky vine eyes for the 2mm wires that stretch along the brick. ‘We tend to go twice round the wire and once round the stem of the rose’. Nutscene garden twine.

Nutscene garden twine.

Troy Scott Smith’s handmade vine eyes based on an old example from the garden.

Troy Scott Smith’s handmade vine eyes based on an old example from the garden.

When the roses have been pruned they are given fertiliser (Sissinghurst has its own recipe: 2 parts Sulphate of Potash to 1 part Kieserite), and then a layer of compost – ‘compost is an underrated thing’ sighs Troy – is spread at the base of the plant. Once the buds have started to break in mid March, a fortnightly spraying regime begins – it takes two gardeners two hours to get round the extensive rose collection. There is a wisdom combined with an experimental curiosity in Troy’s approach which I will see again and again over the course of the morning. He will try out different combinations of traditional fungicides and Savona soap solution and regularly sprays with liquid seaweed feed or SB Plant Invigorator (which is new to me and looks impressive) too. ‘We pause for the main flowering period June, July. Last year we did a little bit of an experiment where we didn’t spray a number of roses for the last part of the summer’. The blackspot and rust came back with vigour but he is happy that he has tried.

SB Plant Invigorator.

Against the entrance arch the octogenarian ‘Alistair Stella Gray’ is not as vigorous as it used to be so instead of trying to get it to stretch over the entire arch it has been ‘retreated’ to one side and a new ‘Alistair Stella Gray’ planted on the opposite side of the arch so that the two can meet.

Ageing plants provide a constant challenge for Troy and his team throughout the garden. In the White Garden there is a famous central arbour smothered in Rosa mulligani .

Rosa mulliganii in flower.

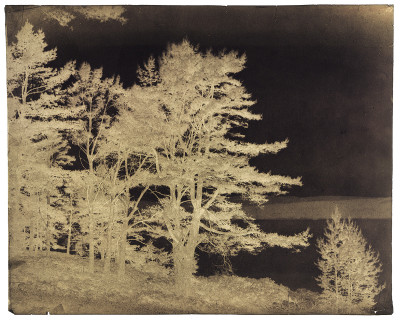

In fact, to maintain a spectacular display of this fragrant rose (believed to be the biggest of climbing rose available in the UK), there are now three roses, the original one, a second one planted by the previous Sissinghurst Head Gardener, Alexis Datta, and now Troy has added a third rose – all trained over the iron arbour designed by Nigel Nicholson, with assistance from rose expert Graham Stuart Thomas, when the original rose was at its most vigorous. The pruning regime of the three roses remains the same with the aim of producing spare, dancing ‘living lace’ that stops the heart on this cold winter day and will produce an incredible frothing canopy of white in midsummer.

The Rosa muliganii arbour in The White Garden – the stems of the rose are pruned into heartstoppingly beautiful ‘Living Lace’.

The Rosa muliganii arbour in The White Garden – the stems of the rose are pruned into heartstoppingly beautiful ‘Living Lace’.

Elsewhere in the garden the same looping pruning discipline prevails – against walls, next to a spur-pruned apple tree at the back of the shop, along strong wire to create a stand alone rose ‘fence’ and, looking particularly handsome on this grey January day, against the white clapboard building next to the café:

The Sissinghurst ‘living lace’ style of rose pruning against walls and fences.

In the walled Rose Garden the shrub roses are supposed to be finished by the end of the week. There is a rhythmic calm as the team (there are six full time gardeners, two part time gardeners and a number of invaluable volunteers) make their way through the space, pruning and clearing as they go, creating a low creeping world of supple crinolines and elegant towers. The crinolines are created by arching the new, flexible stems into semi-circles and training these onto hazel hoops or ‘benders’ in the ground.

Shrub roses, trained into Louise Bourgoi-like spider shapes, take over the Rose Garden.

Shrub roses, trained into Louise Bourgoi-like spider shapes, take over the Rose Garden.

The South facing Rose Garden walls are dizzy with fabulously tangled figs. It is fascinating to see, again, how crucial curves are to achieve the right sort of comfortable fullness when the figs come into leaf. Pruning the figs is a finely judged matter – it takes place as late as possible at Sissinghurst because of the tenderness of the figs. But in a warm spell the leaves break fast so when the moment comes the walls need to be tackled at speed.

The fabulously tangled wall trained figs – pruning to take place as late as possible.

As we watch the steady transformation of the taller shrub roses from stands of impenetrable shagginess to clearly defined towers with neat scalloped frames, Troy explains his plans to reintroduce an avenue of cherry trees into the Rose Garden. Despite extensive research, it is not known which cherries Vita Sackville-West originally planted so he has decided on the winter flowering cherry (Prunus subhirtella autumnalis) which she is known to have liked and which crucially has a reasonably light canopy. Obviously the moment you plant trees in a border there will be a knock-on effect on the planting beneath it … …’The only problem with the winter flowering cherry is that visitors won’t really see it’ he adds with a slightly anxious laugh (giving me a glimpse for a moment of the incredible number of ingredients that must be juggled for every decision made in this world famous, historic garden), but then he is reassured by the fact that the Rose Garden can be seen from the Tower and glimpsed en route to the the newly open-to-the-public South Cottage, both of which are open throughout the winter.

The transformation of a taller shrub rose.

The transformation of a taller shrub rose.

The compact boards which are used throughout the borders during pruning to protect the heavy clay soil.

As I walk to take in the famous view from the Tower I am reminded that there is one rose in the garden which will not, of course, be pruned until just after it has flowered. The thornless evergreen rambler, Rosa banksiae ‘Lutea’, is one of the earliest roses to flower – it has clusters of pale lemon flowers in late spring – and at Sissinghurst it forms a delicate screen of foliage in the central arch which beckons you onwards and which will explode into a haze of yellow later in the year.

Rosa banksiae ‘Lutea’ against the arch that separates the Top Courtyard from the Lower Courtyard.

Once at the top of the tower it is a complete pleasure to take in the clean-edged sculptural quality of the yew hedges and the quartet of Irish yews in the garden of South Cottage. If you are ever flagging in your faith in the power of structure in the garden, head to Sissinghurst as early in the year as you can (the entire garden will be open this year from March 11th).

The clean lines of yew hedges especially seen from the Tower.

The clean lines of yew hedges especially seen from the Tower.

Within the garden the hedges play a shifting series of roles. Here, tight clipped yew provides ballast and guides the eye firmly into the distance:

Yew hedges guide the eye firmly into the distance.

Yew hedges guide the eye firmly into the distance.

Elsewhere the velvet green planes provide a wonderful back-drop to red winter stems or the pale silvery buds of magnolia :

Red winter stems and silvery magnolia buds against velvety green yew.

Red winter stems and silvery magnolia buds against velvety green yew.

I love this glimpse of the Herb Garden with pea sticks leaning ready for action against the wooden bench which nestles so comfortably between buttresses of yew. The bleached-out, silvery-mauve aromatic plants remain soft and inviting against the vivid green backdrop.

The Herb Garden.

The Herb Garden.

Not a hedge – obviously – but this mown path through the damp grass of the Orchard has a surprisingly powerful presence.

The serene Orchard path.

The serene Orchard path.

There is a considerable amount of important box hedging in the garden which carries the usual worries of box in the 21st century – plus particular stylistic concerns for this famous garden. Troy is tackling the situation in his characteristic surefooted and gently experimental way. In the White Garden he wants to loosen up the low box edging for a more abundant, relaxed feel – ‘I think Sissinghurst became too tidy’ – but at the same time has to balance the more fitting, softer aesthetic with the level of irritation the narrower paths might bring forth from demanding visitors. He is relaxed about the way the expanding hedges are looking a bit rough around the edges as they are allowed to grow. If there is an ailing section of hedge he moves box plants from elsewhere in the garden to fill the gap (he would not consider introducing new box into the garden now) and, in case the worse happens – ‘I have the sad feeling we will have to take all our box out one day’ – he has just brought in a load of Euonymus japonicus ‘Microphyllus’ (the box leaved euonymus) to trial.

Box edging in the White Garden – beginning to bulge satisfactorily.

Box edging in the White Garden – beginning to bulge satisfactorily.

Elsewhere in the garden the Lion Pond at the base of the old Elizabethan wall is brought alive in winter by the vibrant fresh green of some low box hedging.

The fresh green of a section of box hedging near the Lion Pond gives this area energy at the beginning of the year.

The fresh green of a section of box hedging near the Lion Pond gives this area energy at the beginning of the year.

Yew and pleached lime trees are a vital and anchoring combination both at the front of the Castle and at the approach to the Lime Walk from South Cottage.

Yew hedge and pleached limes at the front of Sissinghurst Castle.

Yew hedge and pleached limes at the front of Sissinghurst Castle.

The four Irish yews in the Cottage Garden are incredibly beautiful at any time of year. In this photograph there is the wonderful extra layering of Irish yew with box drums behind and then a clipped yew hedge directly in front of a section of pleached lime. Rich layering of Irish yew, box, yew hedge and pleached lime in the Cottage Garden

Rich layering of Irish yew, box, yew hedge and pleached lime in the Cottage Garden

The Lime Walk is famous for its immaculate avenue of trained lime trees underplanted with spring bulbs.

The Lime Walk.

The Lime Walk.

But of course nothing about a garden can stand still and it takes a skilled and subtle gardener to tackle the challenges that the Lime Walk quietly but insistently poses. Troy has changed the pruning regime of the trees themselves – bringing the date forward from August to Midsummer’s Day. This brings more light into the walk itself during the summer and leads to a haze of wonderful ruby growth.

Deep red new growth on the lime trees a result of midsummer pruning.

Deep red new growth on the lime trees a result of midsummer pruning.

He is fond of this effect, but at the back of his mind is a slight worry that this pruning regime may perhaps be weakening the trees. At the same time the branches are becoming altogether too long and a further experiment is taking place – luckily on a shorter stretch of lime trees elsewhere in the garden – to reduce the branches considerably .

Then there are the bulb beds underneath the trees. I can see hundreds of Crocus tommasinianus shoots, but my enthusiasm is quickly checked as Troy explains that the crocus has become ‘so aggressive and spread so well that it outcompetes some of the finer tulips and fritillaries’. Sections of border are being taken up each year, cleared, sterilised and then the bulbs (which are planted in mixed groups in pots to create as natural an effect as possible as quickly as possible) are sunk into the beds.

Hundreds of unwanted Crocus tommasinianus shoots in the beds of the Lime Walk.

Then there are questions of opening up the area immediately beyond the Lime Walk so that visitors can stroll down unimpeded to the lake – and how best to do this of course – and beyond the Lime Walk is the Nuttery where the underplanting is also getting out of balance (Troy remembers a lighter, more dancing tapestry of planting when he was here before in 1992-97 ). Added to this, the mostly yellow azalea border across the path is about to be replaced with a much richer palette of azaleas underplanted with brightly coloured polyanthus (which Vita had until 1973) and glamorous peonies and lilies ‘It might be a bit bold in places but you don’t want to be too tasteful’ muses the Head Gardener with a grin.

Silhouette of pleached lime against the sky.

Silhouette of pleached lime against the sky.

The Nuttery – the underplanting is under review so that the epimedium seen here for example does become too dominant.

The Nuttery – the underplanting is under review so that the epimedium seen here for example does become too dominant.

The Azalea Bank left – about to undergo a 1970’s polaroid transformation.

As well as a host of venerable garden advisors and historians, Dan Pearson comes on a voluntary basis twice a year to act as an advisor and sounding board. I can imagine that these are productive and hugely enjoyable days much appreciated even by the most thoughtful of Head Gardeners..

Before I leave the garden I make a note of the straightforward plants which are looking good even at this time of the year. The blue-grey leaved Euphorbia characias is as always looking fresh and strong – such a great architectural plant that always helps an area of the garden look well furnished and happy.

Euphorbia characias adding fullness to the spare winter border against the Elizabethan Wall.

At the entrance to South Cottage Mahonia and Helleborus foetidus look bright and fresh, especially perhaps because they are each given a good amount of space in which to shine.

Mahonia and Helleborus foetidus against the entrance to South Cottage.

Mahonia and Helleborus foetidus against the entrance to South Cottage.

One of my surprise favourites is this fine, spikey pair of Yucca gloriosa which I admit to never having used, but which looks wonderfully at home with box and rosemary at the base of this aged red wall.

Yucca glorious anchoring the entrance border.

One sneaky inclusion in this list is Rosa ‘Meg’ which is also growing at the entrance. It is a rose I have not grown – and which was obviously not in flower! – but which has, I discover, large, almost single, beautifully waved flowers and a delicate pink-apricot colour, with red-gold stamens. It would look wonderful in a garden with my favourite Rosa mutabilis whose flowers pass through shades of apricot yellow to coppery pink.

Rosa ‘Meg’.

Rosa ‘Meg’.

Another new discovery is the rare evergreen shrub Distylium racemosum, or Winter-hazel, which is sunning itself on the left of the central Courtyard archway with some Rosmarinus officinalis ‘Sissinghurst Blue’ bursting out at its feet. I have tracked it down to the wonderful Bluebell Nursery where it has a rave review ‘a slow growing attractive evergreen tree from Japan… in spring attractive, small, red Hamamelis-like flowers with lurid purple stakes appear on the older branches’. One for the shopping list.

Distylium racemosum growing to the left of the Courtyard arch.

The red witch hazel like flowers of Distylium racemosum. (Photograph courtesy of Bluebell Nursery).

The oldest rose in the garden is the ‘Mme Alfred Carrière’ that covers the front of South Cottage. This was the first thing planted by Vita Sackville West in the entire garden and it is this rose that gets ceremoniously pruned first in the middle of October. I was charmed to discover that Vita had determinedly planted the rose before the couple had actually signed the Title Deeds for the Castle, a sort of guarantee to herself that she was going to make a garden here.

It is a move I might employ myself in some lonely country plot in the coming years. Husband, be warned.

Rosa ‘Mme Alfred Carriere’ against South Cottage – the oldest plant in the garden.