SURPRISING GARDENS IN MUSEUM & GALLERIES IN PARIS AND LONDON

Petit Palais garden with pool, palm trees and golden swags.

Petit Palais garden with pool, palm trees and golden swags.

I was so surprised by the iridescent energy of the garden of the Petit Palais when I visited this month that I stayed out much too long taking in the different views, framed here by a pair of heavy leaved palm trees…

Petit Palais Garden – pool and palm trees

Petit Palais Garden – pool and palm trees

…and here, guided by the upward-sweeping branches of the cherry trees with their copper-brown trunks and rosy haze of grasses behind and electric green eyes of just-opening Euphorbia characias in front.

Petit Palais garden – grasses, cherry tree, euphorbia

Petit Palais garden – grasses, cherry tree, euphorbia

It is a freezing, clear-skied January morning in Paris. The vistas are open and enticing, huge expanses of pale grey and blue laced with gold:

Pont Alexandre III, Paris.

Pont Alexandre III, Paris.

A glimpse through a side-door into the empty cavern of a between-exhibitions Grand Palais gets my heart thumping – I am always happily seduced by the heady potential of a rough studio-like space:

Side entrance to the Grand Palais.

Side entrance to the Grand Palais.

Up the steps and through the imposing arch of the gilded Beaux- Arts doorway – The Petit Palais art museum was built in 1900 for the Exhibition Universelle and then completely renovated over four years from 2001-2005 –

Petit Palais entrance.

Petit Palais entrance.

and then into the sweep of sunlit corridors of this entirely circular building, with towering glass doors and windows in every direction.

A series of windows overlooking the Seine.

The floors are entirely of mosaic in subtle shades of rust, green, black and mustard against soft white:

Mosiac floor, entrance hall, Petit Palais.

Mosiac floor, entrance hall, Petit Palais.

The spacious exhibition halls glide seamlessly into a curved outdoor loggia, with a pair of deep blue and white Sèvres porcelain pots on plinths coaxing you on. The swirling mosaic of the floor is punctuated with lovely circular frosted aqua glass sky lights.

External loggia, Petit Palais, with a pair of Sèvres porcelain pots on plinths.

External loggia, Petit Palais, with a pair of Sèvres porcelain pots on plinths.

Even the curving ceiling of the loggia is decorated with a brown-on-gold trellis festooned with powder blue clematis and pink roses:

The Loggia ceiling, Petit Palais.

The Loggia ceiling, Petit Palais.

Looking back against the interior wall of the loggia, the delicate, punched metal chairs and deep green marble tables add just another layer to the subtle grandeur.

Perfectly judged café chairs and table, Petit Palais.

Perfectly judged café chairs and table, Petit Palais.

And then, between the soaring scale of the grey-brown Vosges granite columns, you get your first proper look at the garden.

The Petit Palais garden, framed by Vosges granite columns.

The Petit Palais garden, framed by Vosges granite columns.

If you look up you see the pale gold swags silhouetted against the sky:

Decorative gold swags silhouetted against the sky

If you look across, out into the garden, you begin to get an idea of the intoxicating lushness of the place.

The lush planting of the Petit Palais garden

The lush planting of the Petit Palais garden

This interior courtyard was always intended to provide a breathing place for visitors to the gallery itself. It is a grand but inviting framework for a garden – a deftly designed space with curves and columns of the palest mustard, grey and pink stone, with the deeper tones of the roof tiles and the uplifting gleam of decorative gold.  View along the central axis of the Petit Palais garden.

View along the central axis of the Petit Palais garden.

Curves and columns of the Petit Palais garden.

Curves and columns of the Petit Palais garden.

Close up swirly marble table top and skinny milk-green café chair against strong shapes in pale stone.

Close up swirly marble table top and skinny milk-green café chair against strong shapes in pale stone.

It has a fundamental dynamism which invites you in to explore and – enriched by simply brilliant planting – every view is different.

Palm trees adding structure, gloss and glamour.

Palm trees adding structure, gloss and glamour.

I love the mix of tropical plants with grasses and evergreen shrubs and perennials. Palm trees add structure, gloss, glamour and a constant sense of surprise. I have never seen the delicate scattered flowers of the winter flowering cherry Prunus x subhirtella ‘Autumnalis’ against the weighty arching branches of a banana tree, but here the combination works brilliantly, not least perhaps because of the glint of gold peeping through.

Prunus x subhirtella ‘Autumnalis’ against banana leaves.

Prunus x subhirtella ‘Autumnalis’ against banana leaves.

Tough stalwarts of the shadier garden are employed with confidence and energy. Here the waxy dark green leaves and perky just opening flower buds of Fatsia japonica look fresh and handsome against the golden stone:

Fatsia japonica, Petit Palais garden.

Fatsia japonica, Petit Palais garden.

Euphorbia characias, Acanthus, Fatsia japonica and Bergenia provide an understory for the deciduous trees.

Elsewhere Euphorbia, Acanthus, Bergenia and Yucca plants combine to make a strong rich green understory for the deciduous trees. I have seen photographs of these cherry trees in spring when their vase-shaped branches are covered in deep pink. This is their moment to swan around outrageously like dancers from the Folies Bergères and I would love to catch the sight for myself.

The other surprising element of the garden is the extensive use of grasses. Here is the most elegant use of pampas grass I know, and the Miscanthus sinensis look graceful and distinguished with their pale fragile heads and rosy winter foliage.

Grasses, including Pampas grass Cortaderia selloana & Miscanthus sinensis, Petit Palais garden.

Grasses, including Pampas grass Cortaderia selloana & Miscanthus sinensis, Petit Palais garden.

On either side of the main steps into the garden there are two magnificent fleets of strapping white-painted Versailles planters filled with handsome specimens of palm tree and Magnolia grandiflora:

Versailles planters with specimens of palm and Magnolia grandiflora, Petit Palais garden.

I go into the café to warm up and eat an elegant slice of lemon cake with my coffee. “Bon appétit, Madame” says a guard, who is also taking a break. “You must have become very cold out there”. I can barely feel my fingers, but I have had a brilliant half hour. The guard leaves, bows slightly and wishes me a ‘bonne journée’. I am indeed having a very good day, I think, as I gaze for one more time at the banana leaves and the dancing Miscanthus heads catching the winter light:

Winter heads of Miscanthus sinensis and banana leaves catching the winter sunlight, Petit Palais garden.

Winter heads of Miscanthus sinensis and banana leaves catching the winter sunlight, Petit Palais garden.

Back in London, I am at the Royal Academy on a glowering January day, a week or so before the opening of its ravishing Painting the Modern Garden exhibition. I am still musing about what it takes to make a successful garden within the walls of a gallery or museum.

Royal Academy, Painting the Modern Garden, 30 January – 20 April 2016.

Royal Academy, Painting the Modern Garden, 30 January – 20 April 2016.

Clearly one of the main challenges is to create a garden that will look good all year round, often within a very limited space. I head for the Keeper’s House, now a restaurant, café and bar, open to RA friends until 4pm and after that to everyone. Tom Stuart-Smith created a garden here in 2013 in what he describes as ‘one of those curious architectural left over spaces’ with almost no natural light. His aim was to make the garden feel as if it has been dug out of the space with an ‘almost archaeological’ quality.

First glimpses of the garden from the windows of the sophisticated mohair velvet sofas of the Belle Shenkman room are as vibrant and seductive today as they would be in midsummer.

Views from the Belle Shenkman Room at the Royal Academy onto Tom Stuart-Smith’s garden.

The green of the spreading arms of the 250 year old Australian tree ferns brought into the UK under license is dazzling, and Stuart-Smith is superbly vindicated in his use of his favourite grass, Hakonechloa macra. In its winter form it is a fiery, eye catching streak which lights up the garden further.

You have to go down a flight of stairs to start climbing back into the garden which is elegantly tiered and tiled throughout in dark brick so that the ground and walls are of the same deep earthy tones. The exuberant tree ferns are accompanied only by the hakonecholoa, the low-growing evergreen shrub Pittosporum tobira ‘Nanum’, with just two climbers, Trachelospernum jasminoides and Virginia Creeper for the walls and railings. Here, restraining the planting palette is key.

Ground level views of the Keeper’s House garden, Royal Academy.

Ground level views of the Keeper’s House garden, Royal Academy.

When you look up, the energy of the tree ferns is celebratory and infectious.

Looking upwards, Keeper’s House garden, Royal Academy.

Looking upwards, Keeper’s House garden, Royal Academy.

I go back into the gallery and start climbing the stairs. What Tom Stuart-Smith has achieved so cleverly is a garden that delivers from any level in the building. I look down through huge panes of glass from the second floor onto David Nash’s blackened wood sculpture, ‘King and Queen’. The tree ferns and egg-yolk yellow grass are a wonderful foil for these dark figures. This is a fine platform for art and the Academicians must enjoy selecting work for this space.

View onto the Keeper’s House garden, Royal Academy, with ‘King and Queen’ by David Nash.

View onto the Keeper’s House garden, Royal Academy, with ‘King and Queen’ by David Nash.

In 2010 my design partner, Helen Fraser, and I were asked to develop a planting scheme for a new garden at the South London Gallery on the busy Peckham Road.

Exterior of the South London Gallery with and without bus

Exterior of the South London Gallery with and without bus

The Fox Garden was a new space that emerged as part of the 6a architects‘ extension of this constantly innovative contemporary art gallery.

The garden would link the ncafé, NO. 67, with a new building, The Clore Studio, and was flanked on one side by the enormous exterior wall of the main 1891 gallery, and on the other by a tall garden wall. A much simpler proposition than the Petit Palais or Keeper’s House gardens, but nonetheless a rather unevenly lit garden with the need to look good all year round and to offer change throughout the seasons. The noise and grime of the road outside would increase the sense of surprise when the visitor came across the garden for the first time.

Framework of The Fox Garden – the towering gallery wall with elegant new buildings by 6a architects at either end and a wonderful, sinuous brick path.

Framework of The Fox Garden – the towering gallery wall with elegant new buildings by 6a architects at either end and a wonderful, sinuous brick path.

Our solution was use tough, hard-working plants which could create an impact for as long a season as possible. The star plant has perhaps been Nandina domestica – or heavenly bamboo – which has thrived here and provides an almost constant succession of white flower sprays followed by red berries:

Nandina domestica – or heavenly bamboo – creating a lush and welcoming atmosphere in The Fox Garden, South London Gallery on a January day.

Nandina domestica – or heavenly bamboo – creating a lush and welcoming atmosphere in The Fox Garden, South London Gallery on a January day.

We have used three flowering dogwoods – Cornus kousa var Chinensis – including a fabulous almost outsize specimen directly outside the café. These illuminate the garden in June, matching the glamour of Paul Morrison’s covetable gilded wall painting in the café atrium, and provide a period of rich autumn colour.

Cornus kousa var Chinensis – with a close up of the beautiful white bracts which surround the tiny flowerhead.

Cornus kousa var Chinensis – with a close up of the beautiful white bracts which surround the tiny flowerhead.

Views through to the flowering dogwood from the No. 67 dining room with its exhilarating Paul Morrison gold mural.

Claret red autumn colour of the Cornus kousa var Chinensis with Lawrence Weiner’s swooping ‘wall sculture’ on the gallery wall, part of his 2014 ‘All in Due Course’ exhibition.

Claret red autumn colour of the Cornus kousa var Chinensis with Lawrence Weiner’s swooping ‘wall sculture’ on the gallery wall, part of his 2014 ‘All in Due Course’ exhibition.

Other repeated plants are Euphorbia characias with its long lasting lime green bracts… Euphorbia characias with its lime green bracts.

Euphorbia characias with its lime green bracts.

…and Libertia grandiflora which we love for its white flowers in May, long lasting seedheads, and year round architectural presence:

Libertia grandiflora which makes everyone smile the garden in May.

Libertia grandiflora which makes everyone smile the garden in May.

The Libertia even makes Heidi smile – Heidi, gardener of The Fox Garden, is of course the secret ingredient: Heidi – The Fox Garden’s secret ingredient.

Heidi – The Fox Garden’s secret ingredient.

Happily it seems that gardens within museums and cafés are providing so much enjoyment that there are new gardens in development wherever you look. Right here in the South London Gallery a new garden by artist Gabriel Orozco is slowly emerging to be unveiled in the autumn of 2016.

A couple of miles away at the Garden Museum, next to Lambeth Bridge, Dan Pearson is designing a completely new garden within a substantial extension by Dow Jones Architects.

Tradescant Knot Garden, Garden Museum – image thanks to www.culture24.org.uk.

The design has been a challenge, not least because a decision had to be made to lose the knot garden of the existing Tradescant Garden, but Garden Museum director Christopher Woodward tells me ‘Dan has designed a new garden which will try to startle the visitor with unusual shapes and beauties and surprise you with unfamiliar plants … I hope the space with have something of that atmosphere of the Zumpthor-Oudolf pavilion at the Serpentine a few years ago’.

Proposed garden café within the new Dow Jones Architects’ pavilions. Garden to be designed by Dan Pearson. Visualisation by Forbes Massie, image courtesy of The Garden Museum.

Proposed garden café within the new Dow Jones Architects’ pavilions. Garden to be designed by Dan Pearson. Visualisation by Forbes Massie, image courtesy of The Garden Museum.

The Garden Museum is in the safest possible hands with the thoughtful and often magical input of Dan Pearson. The reference to my absolute favourite of the Serpentine Gallery‘s annual summer Pavilions – the 2011 Serpentine Gallery Pavilion designed by architect Peter Zumthor with planting by master plantsman Piet Oudolf – makes the new garden a tantalising prospect.

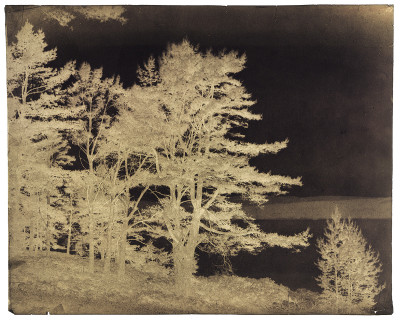

I look through my photographs and find only a few hazy images of my visit to this blackened, open-roofed, box-like cloistered garden that landed for a few summer months next to the Serpentine Gallery in Kensington Gardens. I remember being surprised and deeply cheered by the almost physical pull this hidden garden had on passers-by on a completely beautiful day in an already completely beautiful green space. The contrast between the plain, rather severe building and the planting (which became taller and blousier and more relaxed as the summer wore on) was compelling, and the impact of sunlight and shadows on the space was exciting and dynamic.

Images of the Piet Oudolf planting within the Peter Zumthor Serptentine Gallery Pavilion, September 2011.

Images of the Piet Oudolf planting within the Peter Zumthor Serptentine Gallery Pavilion, September 2011.

I hope that when it is warm again I will have the chance to return to Paris to visit a museum garden that fell off my list on my recent trip. The Musée de la Vie Romantique is housed in a green shuttered villa in Montmartre which belonged to the 19th Century artist, Ary Sheffer. It is said to have a lovely garden and outdoor café with poppies, foxgloves and fragrant roses. I read somewhere that it is the perfect place to sit amongst the roses sipping tea and pretend to be Georges Sand who famously lived nearby. Now this is a whole new angle on museum garden visiting.

A piece I have written for The Daily Telegraph on other gardens to visit in Paris will be published in the Spring.